Global value chains investment and trade for development - agree, remarkable

Global Value Chains and Investment: Changing Dynamics in Asia

The emergence of global value chains (GVCs) during the last 2 decades has implications in many policy areas, starting with trade, investment, and industrial development. The East and Southeast Asia region are key players in the GVCs and account for % of the global inward foreign direct investment (FDI) stock. GVCs are becoming increasingly important in the services sectors, although they are still less developed than in manufacturing.

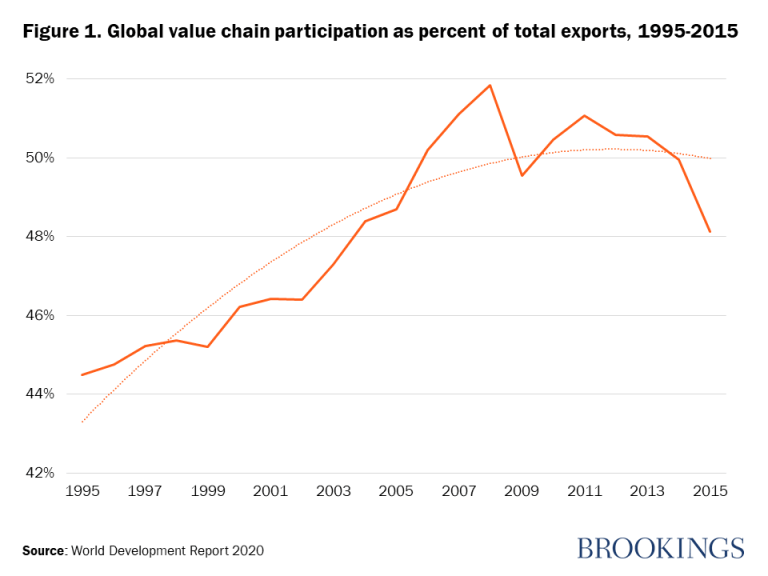

GVC integration since the global financial crisis has continued to increase, but it is still too early to say to what extent GVC integration has been affected by the coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic as rigorous data will only come out with a delay of some years.

Value chains are relatively robust to unexpected changes in trade costs. While the economic shocks related to COVID are indeed severe, the implications of the pandemic are more macroeconomic in nature, with some differences across sectors. The incentive to source goods locally versus using foreign suppliers has not been fundamentally altered.

The policy risk related to reshoring and the change in production locations may also be low. A more likely scenario is targeted interventions in sectors that have assumed particular importance during the pandemic, such as health-related goods and vaccines. Policy responses to the COVID pandemic must recognise the universal nature of the shock. It has affected all countries at essentially the same time, and had broadly similar effects in each of them, at least in its early stages. In this context, trade and investment policies require special review. In the GVC context, trade facilitation can increase backward and forward linkages. Similarly, restrictions on FDI can impair backward GVC participation.

More domestically focused supply chains may not be the right approach to post-COVID GVCs as they are poor shock absorbers. However, supply chain resilience is important for the production of public goods and public health necessities. Any policy intervention must balance the efficiency advantages of GVC production against social objectives.

East and Southeast Asia face a bigger risk in the slow recovery in large, high-income markets of Europe and the United States. Macro-level risks are relatively low, but at a micro level many countries continued use of non-traditional trade policies to introduce de facto discrimination against international suppliers may be a challenge ahead. The major potential change in conditions facing GVCs is the rise of the digital economy; East and Southeast Asia is well positioned to take advantage of these opportunities. Keeping markets relatively open, an effective supplier network, and integrated GVCs are important advantages for Southeast and East Asia in developing the GVCs of the future.

Full Report

GVC and Investment: Changing Dynamics in Asia

Contents

Title page

Table of Contents

List of Figures and Tables

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: GVCs and Investment in Asia: Changing Dynamics and Emerging Trend

Chapter 3: Trade and Investment Policies: Shaping the Future of GVCs

Chapter 4: Post-Covid GVCs in Asia

Chapter 5: Conclusions and Policy Implications + References

About the Authors

<< Back

Источник: [www.oldyorkcellars.com]Industry and globalisation

&#;

International production, trade and investments are increasingly organised within so-called global value chains (GVCs) where the different stages of the production process are located across different countries. Globalisation motivates companies to restructure their operations internationally through outsourcing and offshoring of activities.

Firms try to optimise their production processes by locating the various stages across different sites. The past decades have witnessed a strong trend towards the international dispersion of value chain activities such as design, production, marketing, distribution, etc.

This emergence of GVCs challenges conventional wisdom on how we look at economic globalisation and in particular, the policies that we develop around it.

Papers and policy notes

Policy implications

The OECD provides a broad range of work to help policy makers understand the effects of GVCs on a number of different topics:

Trade in Value-Added

The goods and services we buy are composed of inputs from various countries around the world. However, the flows of goods and services within these global production chains are not always reflected in conventional measures of international trade. The joint OECD – WTO Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) initiative addresses this issue by considering the value added by each country in the production of goods and services that are consumed worldwide. TiVA indicators are designed to better inform policy makers by providing new insights into the commercial relations between nations.

Trade policy and GVCs

Global value chains have become a dominant feature of world trade, encompassing developing, emerging, and developed economies. The whole process of producing goods, from raw materials to finished products, is increasingly carried out wherever the necessary skills and materials are available at competitive cost and quality. Similarly, trade in services is essential for the efficient functioning of GVCs, not only because services link activities across countries but also because they help companies to increase the value of their products. This fragmentation highlights the importance of an ambitious complementary policy agenda to leverage engagement in GVCs into more inclusive growth and employment and the OECD is currently undertaking comprehensive statistical and analytical work that aims to shed light on the scale, nature and consequences of international production sharing.

Initiative on GVCs, production transformation and development

This OECD initiative is a platform for policy dialogue and knowledge sharing between OECD and non-OECD countries. It aims at improving evidence and identifying policy guidelines to promote development by fostering participation and upgrading in global value chains.

&#;

&#;

The evolution of Global Value Chains ()

Introduction

The world economy has undergone significant transformation over the past two decades. During the s, productivity growth, stagnant since the s, appeared to reassert itself, especially in the United States, driven by advances in computing and information technologies. In the early part of the decade, many developing economies experienced a period of rapid economic growth, only to be cut short with the Asian financial crisis in followed by similar crisis in Russia, parts of Latin America and the OPEC countries. The s, which began with a high-tech bust and the terrorist attacks of 9/11, subsequently entered a period of great economic stability that became known as the “great moderation” during which a number of developing economies became known emerging economies,1 and a few of the largest and fastest growing were singled out as the BRICs.2 The “great moderation” ended, however, and the final years of the decade were arguably even more eventful than the early years with a global financial crisis and resulting sharp decline in global trade. Post crisis, the gap in economic performance between rich and emerging economies has widened, the weakness in the fiscal situation among many of the former has become more pronounced, and the global imbalances that had been growing for a number of years have moved to the forefront of many policy debates.

Over these two decades another, but much more gradual, change was also taking place as firms reorganized their business operations into global value chains (GVCs). Although not as apparent as some of the other changes taking place, as this special feature will show, GVCs have exerted a huge impact on world trade and have likely played an important role in many of the developments noted above. For example, GVCs have likely contributed to the rapid growth of the emerging economies, sharpened the decline in world trade during the recent financial crisis but may have also moderated its impact, and will influence the response to global imbalances. And most importantly, GVCs impact on productivity growth, competitiveness, and therefore the standards of living within economies – the fundamental goal of economic progress and policy.

The concept of global value chains (GVCs) was introduced in the special feature contained in Canada’s State of Trade .3 Since then, a significant amount of research and analysis has been devoted to understanding GVCs and how they work. This year’s special feature provides an overview of some of that recent work, draws on the latest statistics and attempts to provide a link between GVCs and economic theory.

Putting GVCs in Their Place

A global value chain describes the full range of activities undertaken to bring a product or service from its conception to its end use and how these activities are distributed over geographic space and across international borders.4

This definition offers a structural view of GVCs, presenting themas a series of activities, performed by any number of firms with each activity located in the jurisdiction where it is most efficiently undertaken. This definition describes how GVCs are organized and why. Another view of GVCs, however, might focus on the transactions they generate; for example, the cross-border flow of intermediate goods and services that are combined in a final product that is sold globally. Both definitions can be reconciled with recent developments in economic theory.

Since the economist David Ricardo expressed his views in , international trade theory has been governed by the notion of “comparative advantage,” according to which each participant in trade will specialize in producing the good in which it has comparative advantage. According to Ricardo’s model, the meaning of comparative advantage is expressed as a cost advantage, the source of which is not made explicit, although it is generally interpreted and modeled as an advantage based on differences in technology or geography. The result is the well known example of the exchange of British cloth for Portuguese wine. Heckscher and Ohlin built on this foundation, arguing that differences in what they referred to as “factor endowments” determine differences in relative costs. According to the Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) model, this relationship produces, for example, the result that labour intensive countries should specialize in producing labour-intensive products and capital-intensive countries should focus on capital intensive products.

Both of these classical models recognize that firms and individuals trade, and that differences in technology (Ricardo’s model) or endowments (H-Omodel) are specific to particular locations, i.e. countries. However, under the so-called “new trade theory” developed by Paul Krugman in the s, such differences are no longer the only consideration. According to this theory, even countries that are similar will engage in and benefit from trade providing each specializes and thereby becomes more efficient in production as a result of economies of scale. Again, it is firms or individuals that trade, but the potential gains from specialization are a characteristic of the industry.

Along with economies of scale, geographical proximity is another key element of the new trade theory. Here firms will locate near their customers and their suppliers to reduce transportation costs and gain an advantage over their competitors. Large population centres thus becomemagnets for production, which is self-perpetuating as firms engaged in upstreamand downstream activities follow suit and industrial clusters emerge. But, once again, the differences in transportation costs and the relative importance of being close to suppliers and to customers, i.e. agglomeration effects, are characteristics associated with the industry.

If classical theory focuses on differences in characteristics between locations, and new trade theory focuses on the characteristics of individual industries, then the more recent heterogeneous firmtheory (often called new new trade theory) focuses on the differences between individual firms. New new trade theory recognizes that within a given industry and in a given location, significant variation can exist between firms. Althoughmany firms do not engage in international trade, those that do so tend to bemore productive. Firms that both trade and invest abroad tend to be the most productive.

According to new new trade theory, engaging in international trade enables the best firms to expand and replace weaker firms, resulting in increased productivity, higher wages and improved standards of living. Under both classical and new trade theory, most of the gains from trade occur as a result of themovement of resources between industries,5 whereas new new trade theory suggests thatmost benefits arise fromdifferences within industries, i.e. between firms. According to new new trade theory, trade takes place because of the differences between individual firms which can possess a technology or intellectual property (IP) that makes them better able to compete internationally. This produces a second source of benefit from trade because when individual firms expand, they can spread their fixed costs of innovation across a larger customer base, thereby increasing the incentive to innovate. Such a dynamic benefit that accumulates over time,much like compound interest, can potentially be an important gain from trade.

The idea of global value chains builds on this evolution of the understanding of why and how trade occurs and the resulting impacts. As recognized by new new trade theory, even within a country or industry, firms can operate very differently. One of those differencesmay be how firms integrate into global value chains; if firms produce their own intermediate inputs or if they source them from outside the firm, if their human resource or accounting departments are next door to their production facilities or are located half way around the world. GVCs may therefore explain some of the observed productivity differences between firms as identified under the new new trade theory. But, potentially more importantly, GVCs can be treated like a technology employed by the firm to become more competitive. GVCs help to look into the black box that is the firm and understand how they operate and why.

Several models of GVCs have been developed, each aimed at providing a theoretical framework to predict the behaviour of firms engaged in global trade.6 Feenstra and Hanson (, ) begin with a Heckscher-Ohlin framework but divide the production process for any particular final good or service into activities. These activities are then allocated to the location where they are most efficiently performed. Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg () provide a similar model for trade but focus on tasks instead of activities. The difference between activities and tasks is primarily an issue of aggregation. For example, an activity such as legal services may be separated into distinct tasks, such as the provision of highvalue legal advice or the execution of lower-value administrative duties.7 The implication here is that more routine tasks can be moved abroad while higher-value tasks will be performed domestically. An additional difference between the Feenstra and Hanson and the Grossman and Rossi- Hansberg models centres on the role of the firmitself. In the former, trade is assumed to be conducted at arm’s length (i.e. outsourcing) while in the latter it can be interpreted as a transaction within the firm (i.e. offshoring). Antras (, ) provides an important link between the two by enhancing our understanding of how firms decide where to locate various activities and whether or not to exert direct control (i.e. the decision to perform the activity within the firm or to source it from outside the firm).While thesemodels relymostly on the H-O framework, Baldwin () incorporates trade in tasks into the economic geography framework of new trade theory developed by Krugman and how this relates to Canada’s place within North America.

Thus, while some may argue that with the rise of global value chains, comparative advantage no longer applies, it is clear that, as with prior innovations, each new theory builds on the previous rather than replaces it. The modern structure of trade supports this assertion. As would be expected under the classical models, Canada exports resource and resource-based products because Canada has been “endowed” with significant natural resources such as oil, natural gas,minerals and forests, as well as land and water for producing agricultural products. By contrast, countries with an abundance of cheap labour tend to export labour-intensive products. The gradual shift in production location of labour-intensive products (e.g. textiles, clothing and toys) from advanced economies like the United States to economies like Hong Kong and subsequently to developing economies like China and then increasingly to emerging economies in South-East Asia, seems to support the outcome predicted by classical trade theory. The agglomeration of industries predicted by new trade theory can also be observed, for example, in the auto sector in Southern Ontario, the aerospace sector near Montreal and similar industrial clusters across Canada and around the world. This in turn is augmented by new new trade theory which can explain the observable differences in success between firms within industries and why some firms thrive in certain industries despite apparent odds and can even evolve into global champions. As Globerman () points out, adding the concept of GVCs to theories of trade does not render comparative advantage irrelevant. On the contrary, trade occurring at an increasingly finer level raises the potential for gain. Similarly, if there are gains from economies of scale, then being able to aggregate specialized activities (think for example of the rise of firms specializing in HR activities, operating call centers or providing IT support)may allow for increased gains from scale. In this way, GVCs actually magnify rather than diminish comparative advantage and its associated trade gains.

The Drivers

Declining cost of transportation and communications technologies are widely believed to have driven the rise of GVCs. While this may be the case, little work has actually been undertaken to test this or to understand the drivers of GVCsmore generally. This is an important gap for a number of reasons, but possiblymost critically, if it is not known what drove the rise of GVCs, it will not be possible to know if the trend will continue, stagnate or even reverse and what role, if any, policy can play in shaping the evolution of GVCs.

One component of the GVC and transport cost story is the price of oil. As international transport is a heavy user of oil, there is potentially a link between oil prices and the costs of international trade. After peaking in the late s and early s, the price of oil fell steadily to a low of about US$15 per barrel in In nominal dollars, this fall was modest but in real terms it was significant. It has been argued that an important driver of the growth of GVCs was this fall in oil prices. This trend was of course followed by a sharp rise over the s to peak at nearly US$ prior to the global financial crisis.

Figure: 1

Oil Prices and Global Trade

* U.S. dollars per barrel, near month Cushing future on NYMEX.

Data: WTO and U.S. Department of Energy.

There is, however, little empirical evidence that links the decline in oil prices during the s and s to increased trade and the rise of GVCs. One of the few studies that is consistent with this view is that of Bridgman () which finds that high oil prices can explain a large part of the slowdown in trade growth from to Indeed, there ismuchmore evidence which fails to find that oil prices play an important role in the growth of trade or of GVCs. Furthermore, as oil prices increased by nearly ten-fold fromtrough to peak over the s, there was no decline in international trade or slowing of the growth of GVCs. Although Hillberry () points out that there was a switch from air to ocean transport for some goods during this period, he also notes that the shift was much less pronounced for intermediate inputs, suggesting that GVCs are less subject to oil price movements than are finished goods. In fact from onwards trade and oil prices moved in the same direction: world manufacturing imports, which excludes oil and natural resources (both of which saw their price increase over this period), grew quickly while oil prices were rising sharply.

A simple explanation exists for the lack of evidence supporting the link between higher oil prices and lower trade values. Calculations based on Statistic Canada’s inputoutput tables reveal that for the air transportation and the truck transportation sectors, 22 percent and 25 percent, respectively, of purchased inputs (excluding wages, taxes and subsidies) were spent on fuel.8 While these are fairly sizable sums, the share of transportation among other industries’ inputs is surprisingly small. For example, in Canada’s vehiclemanufacturing industry, percent of purchased inputs (excluding wages, taxes and subsidies) was spent on transportation. Of that, rail transport accounted for just over half and truck transport for about a third. For electronic products manufacturing, just under percent of costs were spent on transportation, with more than 70 percent on air transport. Multiplying these small shares of total costs spent on transportation by the share of the relevant transportation sector’s use of fuels, we see that oil prices account for an extremely small share of the total cost of inputs for most goods.

Figure: 2

International Seaborne Trade

Data: UNCTAD, Review of Maritime Transport,

These estimates derive from statistics for Canada’s domestic and international trade combined. The share of transport in total costs can be much larger for international trade as one would expect given that the distance travelled would be much larger on average and may involve more modes of transportation which adds to the cost. For the United States, transportation costs as a percentage of total input costs for international trade were found to be about 4 percent in (Hummels, ). If fuel costs account for between one fifth to one quarter of total transportation costs, fuel costs will account for only about one percent of the cost of the final good.9 This should not be interpreted, however, tomean that oil prices do not have an impact on international trade or on GVCs. Higher oil prices could indeed have a large impact on certain sectors and markets. Those items with the highest shipping cost-to-value ratio, and the most distant markets, would likely be the most impacted. As noted earlier, rising oil prices have likely already had an impact on choice of transportation modes. Significantly higher oil pricesmay not stop the growth of GVCs, but it could affect their configuration and operation.

Declining costs of transportation, and of sea transport as a result of containerization specifically, has been suggested as a potential driver for the rise of GVCs. The growing volume of goods shipped by container internationally appears to coincide with the rise of the GVC, which is why the two are often associated. From to , the volume of goods shipped by container increased fromjust over million tons to billion tons, a more than six-fold increase. The volume shipped by other means also increased but not by nearly asmuch. The volume share of goods shipped by container increased from 5 percent in (and from almost nothing in ) to 16 percent in

Figure: 3

Share of Canadian Exports by Air to Non-U.S. Destinations,*

* By Value.

Data: Statistics Canada and Transport Canada.

But, the fact that containerized shipping emerged at the same time as GVCs, does not, in and of itself imply causation. An important element of the argument linking containerization to the rise of GVCs is a decline in sea freight costs. Detailed work by Hummels () finds only a modest decline in sea freight transport costs due to containerization after the mid s, after having risen sharply from the late s. Thismodest decline in costs does not appear to be sufficient to explain the rapid rise of trade and of GVCs. However, Hummels does find that the largest impact of the innovation in containerized shippingmay not have been reduced costs in the traditional sense, but rather a reduction in international shipping times. Regardless of whether or not cost savings are expressed in conventional terms,the net economic effect is that faster shipping times yield lower transportation costs— because “time is money.” Hummels (, ) also shows that while containerization use increased, the use of air transportation to ship goods was also rising dramatically as its price declined. The share (by value) of Canadian trade that occurs by air has increased substantially. In , more than one quarter of Canadian exports (by value) to non-U.S. destinations occurred by air. And, this is somewhat understated due the high proportion of resources in Canadian exports, which are generally shipped by sea. The share is substantially higher for more manufactured products, with those sectors that posted the fastest growth in trade in intermediate goods also showing a particularly high use of air transport. The evidence therefore suggests that speed of transport has played an important role in the global fragmentation of production, at least with respect to intermediate goods. Evidence has yet to be established for such a link with respect to services, although services involving themovement of people primarily by air would certainly witness a similar effect.

The case for the role of information and communications technologies (ICTs) is equally complex. The special feature included in the State of Trade report also provided information on telecommunications which illustrated a dramatic fall in telecommunications costs with a particularly sharp decline in recent years. Hillberry () investigates the relationship between telecommunications and information technologies and GVCs. His model is based on that of Jones and Kierzkowski () in which these services are treated as complements to imported intermediate inputs. By linking those sectors that make use of ICT services through input-output tables he is able to compare the usage of ICT services with resulting fragmentation of production. Hillberry, however, is not able to find convincing empirical evidence that ICTs drove fragmentation of production.

Interestingly, Hillberry does find that the entrance of new countries into the global economy, and of formerly communist countries in particular, seems to be an important factor driving the fragmentation of production. He hypothesizes that what may have been most important was the unique characteristics of these countries, namely their relatively low wages but high levels of education, especially in technical fields. But he also notes that this effect had largely run its course by

Although their transition from closed to open economies was less demarcated, the opening of such economies as India or Brazil would have likely played a similar role in the rise of GVCs. In these cases, as well as for the formerly communist countries, the removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers are an important component of “opening”. Baier and Bergstand (), for example, find that reductions in tariff rates were three to four times as important for the growth of global trade as were declining transport costs. Tariff rates are particularly important for GVCs as tariffs can potentially be magnified as they are applied to both inputs as well as the final output. Other barriers to trade (i.e. non-tariff measures and regulatory requirements) are likely to be just as important and would also extend to services.

To summarize, very little systematic empirical work has been performed to assess the drivers of the growth of global value chains and more work is definitely needed on this important topic. The work to date suggests that containerized shipping may have played a role, but developments in air transport were most important for the fragmentation of goods production and would likely play an important role for services as well. Given that air transport is the most expensive way to ship goods and that trade did not appear to be overly impacted by the rise in oil prices over the s, rising oil prices will likely not be the critical factor in determining the continued growth of GVCs. Although ICTs and the declining costs of telecommunications are often cited as a driver for the growth of GVCs, there is currently little hard evidence to support this belief. There is some evidence that formerly communist countries entering the global economy during the past decades was an important factor behind the rise of GVCs, but that effect hasmostly dissipated. Declining tariff rates and more general market opening likely played an important role as well. This last, being directly under the control of policymakers, may prove to be the most important.

Canada and GVCs

No reliable method exists to measure global value chains (GVCs) or to determine how a country such as Canada fits in. Indirect methods must be relied upon instead, such as using existing measures of international commercial engagement, from data presented in the United Nations BEC, and from input-output tables.

Figure: 4

Global Average Applied Tariff Rates on All Products

Data: World Bank.

Making use of existing sources of data, for Canada, it can be seen that trade (exports plus imports) increased about 50 percent faster than nominal GDP over the to period.10 This result indicates the increased importance of international markets to Canada’s economy. Trade in commercial services increased even faster, which likewise illustrates their growing importance. Inward and outward FDI stocks also increased faster than goods trade which supports the idea that international commerce is replacing the increasingly-dated concept that international transactions are mostly about trade. The growing importance of “intellectual” trade is reflected in the burgeoning international flow of royalties, licence fees and R&D innovation. In this regard, Canada is preeminent, an important harbinger for its continued economic success.

Figure: 5

Growth In Global Value Chains in Canada Growth Relative to Canadian GDP,

* For FA Sales and FC sales, period is

Data: Statistics Canada.

The United Nations Broad Economic Classification (BEC) system11 can be used to evaluate broad trends in global value chains. The data are readily available for a wide range of countries but provide only a simple breakdown of capital and goods (intermediate and final). Because it is limited to goods, using the BEC data will miss the more dynamic changes occurring in services trade. That said, goods still account for the bulk of Canada’s international trade.

A simple measure of comparative advantage is to compare the level of exports and imports in a given year with a net surplus representing a sign of comparative advantage. Based on the BEC classification system, by thismeasure Canada is a large net exporter of intermediate goods and net importer of both capital goods and consumer goods, the latter being the stronger. Furthermore, Canadian exports of intermediaries are growing faster than imports while the reverse is true for both consumption and capital goods, implying that the demonstrated comparative advantage in intermediaries is getting stronger. Comparing Canada to the world supports the view that Canada specializes in intermediates. By contrast, the United States, with its large overall deficit in merchandise trade shows a deficit in all three goods categories (services trade, for which the United States posts a surplus, is not included). But, the smallest deficit is in capital equipment. Capital equipment also accounts for a larger share of U.S. exports than the world average, potentially suggesting an advantage in that category.

Figure: 6

Exports by Type

Data: UN Comtrade.

Broad statements like this, however, are of limited value. It is not surprising, for example, to find that Canada has an apparent advantage in intermediates, which includes resources. It is also not a surprise that this advantage seems to be strengthening given the rise in resource prices over the past number of years. A more informative measure of Canada’s participation in global value chains involves the use of data presented in input-output tables, which provide estimates of the proportion of intermediate goods used as inputs in production. Such tables also break down intermediate inputs into imported and domestically produced goods. One disadvantage of these tables is the implicit assumption that a given imported input and its domestically produced equivalent are used in equal proportion in production (i.e. as an input in a manufacturing process) and in consumption (i.e. as a consumer good).

Figure: 7

Share of Imports that are Intermediate Inputs

Data: Statistics Canada.

In terms of the share of imports that are intermediate inputs, a strong trend towards GVCs is not observed. There is a modest increase for the economy as a whole over the s, but this amounts to an increase of only two percentage points, and then falls back somewhat since. For manufactured imports, the share at the end of the series is onlymodestly higher than at the beginning. Thus, according to this measure, imports of final products are growing at about the same rates as intermediate inputs. This corresponds to trends observed in the BEC data which shows intermediates growing about as fast as capital and finished goods.

Another method to measure Canada’s participation in GVCs involves determining the share of intermediate inputs that are imported (as opposed to the composition of imports as in the previous discussion). Here we see exceptionally strong growth. For the total economy the share of imported intermediate inputs in total intermediate inputs nearly doubles from percent in to percent in This is a fairly substantial increase considering the huge value of intermediate inputs in the economy and the many thatwould be considered non-tradable. For manufactured intermediate inputs the increase is even more pronounced, growing from percent in to a peak of percent in before falling back to percent in

Figure: 8

Share of Inputs that are Imported

Data: Statistics Canada.

Input-output tables can also be used to examine Canada’s economic performance with respect to imports of intermediate services inputs. In professional services we see one of the strongest gains with less than 7 percent of intermediate inputs being supplied from abroad in the early s12 to a peak of percent in —a three-fold increase—followed by a sharp decline in the s. The share of professional services in total inputs increased even more dramatically, from percent in the early s to percent in —a nearly five-fold increase. This creates a somewhat more nuanced interpretation of GVCs. Firms used to perform these activities within the firm. As they begin to purchase them from outside, these activities are no longer captured under manufacturing but under services; this also helps to explain the growing share of the service economy in most western economies. It wasn’t only the growth of services, but the shift of some activities from being performed within the firm to outside the firm. But once an activity can be purchased from outside the firm it can also be purchased internationally through either offshoring or outsourcing.

Offshoring and Outsourcing in Canada13

Figure: 9

Professional Service* Inputs

* Engineering, scientific, accounting, legal, advertising software development and misc. services to business.

Data: Statistics Canada.

The concepts of offshoring and outsourcing are intimately related to GVCs. In other words, global value chain is the “noun” that represents a globally interconnected network of activities, while offshoring and outsourcing are the “verbs” that describe the movement of activities as the GVCs are formed and the trade flows these activities generate.

Offshoring is essentially themovement abroad of an activity that continues to be performed within the ownership structure of the firm. For example, amanufacturer closing an assembly plant in Canada and opening another plant in a foreign country is engaged in offshoring. By contrast, inshoring occurs when an activity that was once performed abroad is moved into Canada. Outsourcing occurs when the activity is purchased from a supplier outside the ownership structure of the firm. For example, a call centre is closed in Canada and a contract awarded to a firmthat supplies call centre services from a foreign location. Like offshoring, outsourcing has its opposite—insourcing—which occurs when a firmreplaces a foreign supplierwith a domestic supplier.

Figure: 10

Global Circulation of Business Activities

Data: Statistics Canada – SIBS Survey.

Although there has been a great deal of attention given to offshoring and outsourcing in the media and in policy circles, it turns out that both of these trends are relatively subdued. Possibly even more importantly, the trends appear to be much more circular than is commonly thought; a roughly similar number of activities appear to be moving into Canada as out.

Between and , only percent of companies located in Canada (including foreign companies) offshored a business activity. In the manufacturing sector, the rate was percent— more than twice as great, but still small. More striking, however, is that the movement is circular: nearly the same proportion ( percent) of firms located in Canada and percent of manufacturersmoved activities into Canada (i.e. inshored).14

Within individual industries, there is a high degree of correlation between offshoring and inshoring. This suggests that some industries are simply more footloose than others and as a result aremore likely to move activities both out of Canada as well as into Canada.

Figure: 11

Offshoring and Inshoring in Canadian Manufacturing (percent of firms by industry)

Data: Statistics Canada – SIBS Survey.

Within themanufacturing sector, these industries include those producing electronics and related products, such as household appliances, telephone apparatus and radio and television broadcasting equipment, as well as transportation equipment, and some specialized machinery.

The number of industries for which there is net offshoring (percent of firms indicating that they offshore is greater than the number that inshore) only slightly outweighs the number of industries for which there is net inshoring. Within manufacturing the number of firms moving activities into Canada is greater than those moving activities out of Canada in motor vehicle, broadcasting equipment, communications equipment, pharmaceuticals as well as a number of resource processing sectors. The reverse is true (net offshoring) mainly in electronics producing industries.

Figure: 12

Inshoring and Offshoring of Business Activities in Manufacturing

Data: Statistics Canada – SIBS Survey.

Larger firms15, are far more likely to move activities…both in and out of Canada. From to , percent of largemanufacturing firms relocated activities out of Canada while percent moved activities into Canada, compared to only percent and percent, respectively, for small firms. While large firms were much more likely to offshore activities compared to inshoring activities ( percent compared to percent), small firms were more likely to do the reverse ( percent for offshoring compared to percent for inshoring). In terms of numbers, small firms carry significant weight, but much less so when values are considered.

A key aspect in the conceptual framework of global value chains is the idea of activities. While firms are usually organized by industries (such as the electronics industry) there can be a great deal of variation with respect to how firms organize themselves within an industry. For example, one firm may choose to be an integrated producerwith most activities taking place within the firm and within the home country while a competitor may focus on a few key activities and offshore or outsource much else. The Survey of Innovation and Business Strategy (SIBS) identifies 14 business activities (see chart) that are integral to the operation of most firms.16 Understanding the “footloose” nature of these fourteen activities (i.e. whether or not they are likely to be inshored or outshored) is crucial to understanding how GVCs work, and Canada’s global business operations within them.

Figure: 13

Outsourcing of Business Activities in Manufacturing

Data: Statistics Canada – SIBS Survey.

Of these fourteen activities, the most footloose activity (the activity most likely to be offshored or inshored) is the production of goods. In terms of offshoring, the production of goods was nearly four times as likely to be offshored as the nextmost footloose activity, distribution and logistics. For inshoring, production of goods was about three times as likely to be inshored as the next most common www.oldyorkcellars.coml, firms aremore likely to inshore than offshore provision of services as well as distribution and logistics, call centers and R&D, which may suggest that Canada has a comparative advantage in these activities. On the other hand, net offshoring is observed in data processing, ICT, legal and accounting services, among others. Calculations of net inshoring or offshoring must be interpreted with caution as we only have figures of the number of firms having offshored or inshored and not the scale of the activities being moved.

| Motivation | Respondents |

|---|---|

| Non-Labour Costs | % |

| Labour Costs | % |

| Delivery Times | % |

| Access to Knowledge | % |

| Logistics | % |

| Focus on Core Business | % |

| New goods or services | % |

| Following comp or clients | % |

| Tax or Financial | % |

| Lack of Labour | % |

| Other | % |

Data: Statistics Canada – SIBS Survey.

Outsourcing involves buying a good or service from abroad that may have at one point been produced internally or contracted out to a Canadian company.17 Not surprisingly, this is far more common than offshoring as it does not involve equity ownership of operations abroad. Overall, percent of firms outsourced between and , but the share was much higher for manufacturers, of which percent outsourced over that period. By comparison, only percent of firms and percent ofmanufacturers offshored over the same period.

For manufacturers, the most common activity to be outsourced is the production of goods, followed by provision of services, distribution & logistics and marketing and sales. These results also reveal information about the types of activities that companies tend to like to do themselves abroad and those that they are willing to buy at arms length. Formanufacturers, legal services are far more likely to be purchased at arms length as indicated by the relatively high share in outsourcing ( percent) compared to offshoring ( percent). This is a reassuring result given the known preference for frequently hiring outside legal counsel, particularly in foreign markets. There is also a strong preference for contracting the provision of services, production of goods, and software development. By contrast, companies aremore likely to retain financialmanagement, HR and accounting services in-house.

Firms participating in the SIBS survey that either outsourced or offshored activities indicated that by far themost important reason for doing so was cost. Reduction of nonlabour cost was indicated as the most important factor while reduction of labour costswas ranked second. Thiswas the case for manufacturers and non-manufacturers alike. Although substantially less important than costs, access to new markets was cited by manufacturers as the third most important factorwhile non-manufacturers ranked access to specialized knowledge and technologies third. Both groups indicated that lack of available labour, and taxes or other financial incentives were not particularly important factors. These results show that, and as one might expect, themost important factor driving firms to outsource is indeed costs. This also supports the view that it is predominantly pull factors that drive offshoring and outsourcing: the emergence of large supplies of low-cost labour, as well as large and growing markets are driving offshoring and outsourcing, rather than push factors that make Canada an unappealing location fromwhich to do business. Again, this would be consistentwith the earlier findings that thesemovements are part of a circular flow and not a one-way exodus.

| Obstacles | Firms |

|---|---|

| Distance to producers | % |

| Identifying providers | % |

| Language or cultural | % |

| Tariffs | % |

| Foreign legal or admin | % |

| Lack of mgmt expertise | % |

| Cnd Legal or Admin. | % |

| Distance to customers | % |

| Concerns of employees | % |

| Lack of financing | % |

| Tax | % |

| International standards | % |

| Social Values | % |

| IP | % |

Data: Statistics Canada – SIBS Survey.

Roughly one fifth of firms surveyed indicated that they encountered obstacles when conducting offshoring or outsourcing. Interestingly, the proportion was about the same for small firms compared to the average. For respondents overall, foreign legal or administrative obstacles were identified as beingmost significant, followed by language or cultural barriers and distance to producers. Formanufacturers (shown) the prioritieswere somewhat different. Distance to producers was identified as the most important barrier followed by difficulties in identifying potential or suitable suppliers and language or cultural barriers.18 For both manufacturers and non-manufacturers alike, identifying suppliers and dealing with language and cultural issues and foreign legal or administrative issues were identified as being significant, which supports the role of the Canadian trade commissioner service (TCS) in overcoming these obstacles. Tariffs also rank among the top obstacles for manufacturing firms, suggesting the need for continued tariff reductions. Interestingly, concerns about offshoring and outsourcing conflicting with social values, concerns of employees and IP concerns were all identified as least important for both groups, which may point to the ability of firms to address those issues themselves.

Conclusions

Global production is increasingly being governed by global value chains (GVCs). The rise of GVCs has been driven by both technological as well as policy developments. While improvements in ICT and falling costs of transportation and telecommunications have likely played an important role, solid empirical support is still lacking. Only the important role of air transportation has been well established and even here a greater understanding is required, particularly for services trade. Among the policy drivers, the integration of new participants into the global economy has been found to be an important driver as has the related declining tariff rates and other barriers to trade.

There is good reason to believe that all participants, including Canada, are benefiting from the emergence of global value chains. Trade at amore fragmented level and in servicesmagnifies the potential gains from trade. Indeed, Canadian companies and workers can benefit as some low-skilled activities are offshored, which increases the productivity and competitiveness of Canadian companies and translates intomore and better paying jobs for Canadians. This is supported by the data, which show that as some activities are offshored, others are inshored.

The extent to which Canada can prosper within this rapidly changing global economic landscape will depend on Canada’s ability to create an economic environment that attracts and retains high-valued activities that will ensure a high and improving standard of living for all Canadians.

References

Alajääskö, Pekka, () “ Features of International Sourcing in Europe in ” Eurostat, Statistics in focus 73/

Antras, Pol (), “Property Rights and the International Organization of Production”, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings, 95 (2), pp.

Baier, Scott L. and Jeffrey H Bergstrand (), “The growth of world trade: tariffs, transport costs, and income similarity” Journal of International Economics 53 ()

Baldwin, Richard (), “Integration of the North American Economy and New-paradigm Globalization”, in Aaron Sydor (ed) Global Value Chains: Impacts and Implications, Forthcoming.

Baldwin, Richard (), “Integration of the North American Economy and New-paradigm Globalization” Policy Research InitiativeWP

Bridgman, Benjamin (), “Energy prices and the expansion of world trade,” Review of Economic Dynamics 11(4), October:

Caves, Richard E. (), “International Corporations: The Industrial Economics of Foreign Investment,” Economica.

De Backer, Koen and Norihiko Yamano (), “International Comparative Evidence on Global Value Chains”, in Global Value Chains: Impacts and Implications, Forthcoming.

Dunning, John H. (), “Trade, Location of Economic Activity and the MNE: A Search for an Eclectic Approach,” in Bertil Ohlin, Per Ove Hesselborn and Per Magnus Wijkman (eds.), The International Allocation of Economic Activity, London: Macmillan,

Feenstra, Robert (), “Integration of Trade and Disintegration of Production in the Global Economy”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Fall, pp

Globerman, Steven () “Global Value Chains: Economic and Policy Issues”, in Global Value Chains: Impacts and Implications, Forthcoming.

Grossman, Gene and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg (), “ Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory Of Offshoring”, American Economic Review, 98 (5), pp.

Helpman, Elhanan, Marc J. Melitz and Stephen R. Yeaple (), “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms,” American Economic Review 94(1), March:

Helpman, Elhanan (), “A simple theory of international trade with multinational corporations,” Journal of Political Economy 92(3): –

Hillberry, Russel H (), “Causes of International Production Fragmentation: Some Evidence”, in Global Value Chains: Impacts and Implications, Forthcoming.

Hummels, David (), “Transportation Costs and International Trade in the Second Era of Globalization,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3), Summer: –

Hummels, David (), “Time as a Trade Barrier” Unpublished paper, Purdue University.

Jones, R.W. and H. Kierzkowski (), “The Role of Services in Production and International Trade: A Theoretical Framework” in R.W. Jones & A.O. Krueger (Eds), The Political Economy of International Trade: Essays in Honour of R.E. Baldwin, Oxford.

Krugman, Paul (), “Intra-industry Specialization and the Gains from Trade”, Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), October:

Krugman, Paul (), “Scale Economies, Product Differentiation and the Pattern of Trade”, American Economic Review, 70(5), December:

Krugman, Paul (), “Increasing Returns, Monopolistic Competition, and International Trade”, Journal of International Economics, 9, November:

Porter,Michael E. (), “The Competitive Advantage of Nations”, Free Press.

Sydor, Aaron (), “The Rise of Global Value Chains”, Canada’s State of Trade: Trade and Investment Update – , Ottawa: Minister of PublicWorks and Government Services Canada:

Treffler, Daniel (), “Policy Responses to the New Offshoring: Think Globally, Invest Locally”, Ottawa: Industry Canada Working Paper Series, Nov. 25,

- Date Modified:

Global value chain

A global value chain (GVC) refers to the full range of activities that economic actors engaged in to bring a product to market.[1] The global value chain does not only involve production processes, but preproduction (such as design) and postproduction processes (such as marketing and distribution).[1]

GVC is similar to Industry Level Value Chain but encompasses operations at the global level. GVC is similar to the concept of a supply chain, but the latter focuses on conveyance of materials and products between locations, often including change of ownership of those materials and products.[2] The existence of a global value chain (i.e. where different stages in the production and consumption of materials and products of value take place in different parts of the world) implies a global supply chain engaged in the movement of those materials and products on a global basis.

In development[edit]

The first references to the concept of a global value chain date from the mids. Early references were enthusiastic about the upgrading prospects for developing countries that joined them. In his early work based on research on East Asian garment firms, Gary Gereffi, the pioneer in value chain analysis, describes a process of almost ‘natural’ learning and upgrading for the firms which participated in GVCs.[3] This echoed the ‘export-led’ discourse of the World Bank in the ‘East Asian Miracle’ report based on the East Asian ‘Tigers’ success. In economics, GVC was first formalized in a paper by Hummels, Ishii and Yi in [4] They defined GVC as the foreign component of imported intermediate inputs used to produce output, and some fraction of output is subsequently exported. Allowing for such a framework, Kei-Mu Yi showed in a paper that the growth of world trade can be explained with moderate changes in the trade costs and named this phenomenon "vertical specialization".[5]

This encouraged the World Bank and other leading institutions to encourage developing firms to develop their indigenous capabilities through a process of upgrading technical capabilities to meet global standards with leading multinational enterprises (MNE) playing a key role in helping local firms through transfer of new technology, skills and knowledge.

Wider adoption of open source hardware technology used for digital fabrication such as 3D printers like the RepRap has the potential to partially reverse the trend towards global specialization of production systems into elements that may be geographically dispersed and closer to the end users (localization) and thus disrupt global value chains.[6]

Analytical framework[edit]

Global value chains are networks of production and trade across countries. The study of global value chains requires inevitably a trade theory that can treat input trade. However, mainstream trade theories (Heckshcer-Ohlin-Samuelson model and New trade theory and New new trade theory) are only concerned with final goods. It needs a New new new trade theory.[7] Escaith and Miroudot estimates that the Ricardian trade model in its extended form has "the advantage" of being better suited to the analysis of global value chains.[8]

The lack of appropriate tool of analysis, the studies of GVCs have been conducted mainly by sociologists like Gary Gereffi,[9] and management science researchers.[10][11] See for a genealogy Jennifer Bair ().[12] Studies by means of global Input-Output Table is starting.[13][14]

Development and upgrading[edit]

GVCs become a major topic in development economics especially for middle-income countries, because the "upgrading" within GVCs became the crucial condition for the sustained growth of those countries.[15][16]

GVC analysis views “upgrading” as a continuum starting with “process upgrading” (e.g. a producer adopts better technology to improve efficiency), then moves on to “product upgrading” where the quality or functionality of the product is upgraded by using higher quality material or a better quality management system (QMS), and then on to “functional upgrading” in which the firm begins to design its own product and develops marketing and branding capabilities and begins to supply to end markets/customers directly - often by targeting geographies or customers (which are not served by its existing multinational clients). Subsequently, the process of upgrading might also cover inter-sectoral upgrading.[17]

Functional upgrading to high-value-added activities like design and branding is for developing country suppliers a key opportunity to achieve higher profits in GCV. Likewise, a review of the empirical literature highlighted that suppliers operating in unstable economies, like Pakistan and Bangladesh, face high barriers to reach functional upgrading in high-value-added activities.[18]

This upgrading process in GVCs has been challenged by other researchers – some of whom argue that insertion in global value chains does not always lead to upgrading. Some authors[19] argue that the expected upgrading process might not hold for all types of upgrading. Specifically they argue upgrading into design, marketing and branding might be hindered by exporting under certain conditions because MNEs have no interest in transferring these core skills to their suppliers thus preventing them from accessing global markets (except as a supplier) for first world customer.

Current research on governance and its impact from a development perspective[edit]

There are motivations behind renewed interest in global value chains and the opportunities that they may present for countries in South Asia. A report found that looking at the production chain, rather than the individual stages of production, is more helpful. Individual donors with their own priorities and expertise cannot be expected to provide comprehensive response to the needs identified, not to mention the legal responsibilities of many specialist agencies. The research suggests they adjust their priorities and modalities to the way production chains operate, and to coordinate with other donors to cover all trade needs. It calls for donors and governments to work together to assess how aid flows may affect power relationships.[20]

In his paper, Gereffi identified two major types of governance. The first were buyer-driven chains, where the lead firms are final buyers such as retail chains and branded product producers such as non-durable final consumer products (e.g., clothing, footwear and food). The second governance type identified by Gereffi were producer-driven chains. Here the technological competences of the lead firms (generally upstream in the chain) defined the chain's competitiveness.

Current research suggests that GVCs exhibit a variety of characteristics and impact communities in a variety of ways. In a paper that emerged from the deliberations of the GVC Initiative,[21] five GVC governance patterns were identified:

- Hierarchical chains represent the fully internalized operations of vertically integrated firms.

- Quasi-hierarchical (or captive chains) involve suppliers or intermediate customers with low levels of capabilities, who require high levels of support and are the subject of well-developed supply chain management from lead firms (often called the chain governor).

- Relational and modular chain governance exhibit durable relations between lead firms and their suppliers and customers in the chain, but with low levels of chain governance often because the main suppliers in the chain possess their own unique competences (and/or infrastructure) and can operate independently of the lead firm.

- Market chains represent the classic arms length relationships found in many commodity markets.

As capabilities in many low- and middle-income economies have grown, chain governance has tended to move away from quasi-hierarchical models toward modular type as this form of governance reduces the costs of supply chain management and allows chain governors to maintain a healthy level of competition in their supply chains. However, whilst it maintains short-term competition in the supply chain, it has allowed some leading intermediaries to develop considerable functional competences (e.g., design and branding). In the long term these have the potential to emerge as competitors to their original chain governor.[22] Other study outlines the initiative to promote inclusive GVC,[23] three GVC patterns were identified:

The theoretical concepts often considered firms as operating in a single value chain (with a single customer). Whilst this was often the case in quasi-hierarchical chains (with considerable customer power) it has become apparent that some firms operate in multiple value chains (subject to multiple forms of governance) and serve both national and international markets and that this plays a role in the development of firm capabilities.[24][25] The recent trend in GVC research shows exploration of issue emerging from the interaction of different stakeholders from within and outside the GVC structures and their effects on the sustainability of the GVCs. For examples, the local governance institutions and production firms.[26]

Summary of Unctad report: global value chains and development[edit]

In , UNCTAD published two reports on GVCs and their contribution to development. They concluded that:[25]

- GVCs make a significant contribution to international development. Value-added trade contributes about 30% to the GDP of developing countries, significantly more than it does in developed countries (18%) furthermore the level of participation in GVCs is associated with stronger levels of GDP per capita growth. GVCs thus have a direct impact on the economy, employment and income and create opportunities for development. They can also be an important mechanism for developing countries to enhance productive capacity, by increasing the rate of adoption of technology and through workforce skill development, thus building the foundations for long-term industrial upgrading.

- However, there are limitations to the GVC approach. Their contribution to the growth may be limited if the work done in-country is relatively low value adding (i.e. contributes only a small part of the total value added for the product or service). In addition there is no automatic process that guarantees diffusion of technology, skill-building and upgrading. Developing countries thus face the risk of operating in permanently low value-added activities. Finally, there are potential negative impacts on the environment and social conditions, including: poor workplace conditions, occupational safety and health, and job security. The relative ease with which the Value Chain Governors can relocate their production (often to lower cost countries) also create additional risks.

- Countries need to carefully assess the pros and cons of GVC participation and the costs and benefits of proactive policies to promote GVCs or GVC-led development strategies. Promoting GVC participation implies targeting specific GVC segments and GVC participation can only form one part of a country's overall development strategy.

- Before promoting GVC participation, policymakers should evaluate their countries’ trade profiles and industrial capabilities in order to select strategic GVC development paths. Achieving upgrading opportunities through CVCs requires a structured approach that includes:

- embedding GVCs in industrial development policies (e.g. targeting GVC tasks and activities);

- enabling GVC growth by providing the right framework conditions for trade and FDI and by putting in place the needed infrastructure; and

- developing firm capabilities and training the local workforce.

Gender and global value chains[edit]

Main article: Global care chain

Gender plays a prominent role in global value chains, because it influences consumption patterns within the United States, and thus affects production on a larger scale. In turn, specific roles within the value chain are also determined by gender, making gender a key component in the process as well. Far more women than men are found in the informal sector, as self-employed workers or subcontractors, while specific jobs and broader fields of work differ between men and women.[27]

Sustainability and global value chains[edit]

Sustainability is an increasingly important factor in global value chains, and there is a growing need to evaluate their performance based on social and environmental impact, as well as economic. Initiatives such as The United NationsSustainable Development Goals encourage sustainable practices through its goal blueprint, but there are few enforced policies which address sustainability with the urgency required to protect natural resources and reduce the impacts of climate change on a global scale. Sustainability efforts in global value chains are often voluntary steps taken in the private sector, such as the use of sustainability standards and certifications, and ecolabels, but they can sometimes lack evidence of measurable sustainable impacts. For example, some ecolabels seek to address issues such as poverty. Yet in some cases, even if producers meet ecolabel standards, the burden of certification costs can end up reducing the overall income for these producers. [28] The measurement of sustainability in global value chains requires a multifaceted assessment which includes environmental, social and economic impacts, and it must also be standardized enough to be compared in order to generate sufficient learning and for scalability. Technologies that make these types of measurements are becoming both more available and essential for the public and private sector sustainability efforts.[29] Besides, the recent finding shows that the local realities like governance system and institutions also play a significant role in economic sustainability of the global value chains.[30] Implementation of sustainability policies at the global level demands the greening of supply chains in their entirety, as well as their comprehensive technological modernization to accommodate advancing trends such as digitization, artificial intelligence (AI), and big data.[31]

Negative impacts of global value chains[edit]

Global supply chain management is facing the increasing difficulty in predicting demand variability in different areas. In addition, managing the production and transportation of goods over large distances to meet the peak demand represents another challenge.[32]

Integrating global value chains requires all actors to adapt to technological changes, which is capital-intensive. Therefore, it is safe to say that this trend significantly benefits developed countries rather than developing countries.[33]

Shifting of production base by the lead firm raises the challenges of sustainability for the local firms (economy) and the labor (society).[34]

Data and Software[edit]

OECD maintains Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables, the most recent update was November [35] An earlier project started at the University of Groningen.[36]GTAP maintains a software program with an included trade database. Open-source software in R includes the decompr[37] and gvc packages.[38]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abKim, Soo Yeon; Rosendorff, B. Peter (). "Firms, states, and global production". Economics & Politics. 33 (3): – doi/ecpo ISSN&#;

- ^Wang, J., Comparing Value Chain and Supply Chain, Q Stock Inventory, accessed 19 November

- ^Gereffi, G., (). The Organisation of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How US Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks. In G. Gereffi, and M. Korzeniewicz (Eds), Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- ^Hummels, David; Ishii, Jun; Yi, Kei-Mu (). "The nature and growth of vertical specialization in world trade". Journal of International Economics. 54 (1): 75– doi/S(00) ISSN&#;

- ^Yi, Kei‐Mu (). "Can Vertical Specialization Explain the Growth of World Trade?". Journal of Political Economy. (1): 52– doi/ ISSN&#; S2CID&#;

- ^André O. Laplume; Bent Petersen; Joshua M. Pearce (). "Global value chains from a 3D printing perspective". Journal of International Business Studies. 47 (5): – doi/jibs S2CID&#;

- ^Inomata, S. (). "Chapter 1: Analytical frameworks for global value chains: An overview (The global value chain paradigm: New-New-New Trade Theory?)"(PDF). Global Value Chain Development Report Measuring and Analyzing the Impact of GVCs on Economic Development. p.&#; ISBN&#;.

- ^Escaith, H.; Miroudot, S. (). Industry-level competitiveness and Inefficiency spillovers in global value chains(PDF). 24th International Input-Output Conference July , Seoul, Korea.

- ^Gary Gereffi (). Global Value Chains and Development. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^Sturgeon and Kawakami

- ^Hertenstein, Peter (). Multinationals, Global Value Chains and Governance: The Mechanics of Power in Inter-Firm Relations. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. ISBN&#;.

- ^Jennifer Bair () Global Commodity Chains: Genealogy and Review. In J. Bair (Ed.) Frontiers of Commodity Chain Research. Stanford University Press, Stanford: California.

- ^H. Escaith and S. Inomata () Global Value Chains in East Asia: The Role of Industrial Networks and Trade Policies. In D. Elms and P. Low (Eds.) Global Value Chains in a Changing World, WTO, Geneva.

- ^H. Escaith () Mapping Global Value Chains and Measuring Trade in Tasks. B. Ferrarini and D. Hummels Asia and Global Production Networks: Implications for Trade, Incomes and Economic Vulnerability. Mandaluyong, Philippines and Cheltenham, UKK: Asian Development Bank and Edward Elgar Publishing.

- ^Keun Lee () Economic Catch-Up and Technological Leapfrogging: The Path to Development and Macroeconomic Stability in Korea. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham: UK and Northermpsuon: Mass. Keun Lee () The Art of Economic Catch-Up: Barrieres, Detours and Leapfrogging. Cambridge University Press.

- ^Lee, Keun; Szapiro, Marina; Mao, Zhuqing (14 October ). "From Global Value Chains (GVC) to Innovation Systems for Local Value Chains and Knowledge Creation". The European Journal of Development Research. 30 (3): – doi/s S2CID&#;

- ^Humphrey, J., and H. Schmitz. "Chain Governance and Upgrading: Taking Stock". in Local Enterprises in the Global Economy, edited by H. Schmitz, – Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- ^Choksy, Umair Shafi; Sinkovics, Noemi; Sinkovics, Rudolf R. (November 2, ). "Exploring the relationship between upgrading and capturing profits from GVC participation for disadvantaged suppliers in developing countries". Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences-Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l'Administration (in French and English). Wilhey Online Library. 34 (4): – doi/cjas ISSN&#; OCLC&#; Retrieved July 22,

- ^Humphrey, J. and Schmitz, H. (). Governance and Upgrading: Linking Industrial Cluster and Global Value Chain. IDS Working Paper , Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton.

- ^Jodie Keane (). "Aid for trade and Global Value Chains: Issues for South Asia"(PDF). Policy Brief. No.&#; SAWTEE. Retrieved 19 April &#; via www.oldyorkcellars.com

- ^Gary Gereffi, John Humphrey, and Timothy Sturgeon, “The governance of global value chains,” Review of International Political Economy, vol. 12, no. 1,

- ^Kaplinsky, R. (), The Role of Standards in Global Value Chains and their Impact on Economic and Social Upgrading, Policy Research Paper , World Bank

- ^A.H. Pratono, “Cross-cultural collaboration for inclusive global value chain: a case study of rattan industry,” International Journal of Emerging Markets, vol. 12, no. 1,

- ^Navas-Aleman, L. (). "The Impact of Operating in Multiple Value Chains for Upgrading: The Case of the Brazilian Furniture and Footwear Industries". World Development. 39 (8): – doi/www.oldyorkcellars.comev

- ^ abWorld Investment Report Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development(PDF). Switzerland: United Nations. ISBN&#;. Retrieved 19 April &#; via www.oldyorkcellars.com

- ^Asghar, Ali; Kalim, Rukhsana (). "The Role of Institutions in the Economic Sustainability of Global Value Chains: A Transcendental Phenomenological Analysis of Pakistani Apparel Industry". Journal of Applied Economics and Business Studies. 3 (1): 1– doi/jaebs ISSN&#;

- ^Carr, Marilyn; Chen, Martha Alter; Tate, Jane (). "Globalization and Home-Based Workers". Feminist Economics. 6 (3): – doi/ S2CID&#;

- ^"Meeting Sustainability Goals: Voluntary Sustainability Standards and the Role of the Government". Pacific Institute. Retrieved

- ^Giovannucci, Daniele; Hansmann, Berthold; Palekhov, Dmitry; Schmidt, Michael (), Schmidt, Michael; Giovannucci, Daniele; Palekhov, Dmitry; Hansmann, Berthold (eds.), "The Editors Review of Evidence and Perspectives on Sustainable Global Value Chains", Sustainable Global Value Chains, Natural Resource Management in Transition, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp.&#;1–15, doi/_1, ISBN&#;

- ^Asghar, Ali; Kalim, Rukhsana (). "The Role of Institutions in the Economic Sustainability of Global Value Chains: A Transcendental Phenomenological Analysis of Pakistani Apparel Industry". Journal of Applied Economics and Business Studies. 3 (1): 1– doi/jaebs ISSN&#;

- ^Sanders, Nada R.; Boone, Tonya; Ganeshan, Ram; Wood, John D. (). "Sustainable Supply Chains in the Age of AI and Digitization: Research Challenges and Opportunities". Journal of Business Logistics. 40 (3): – doi/jbl ISSN&#;

- ^"What are the biggest challenges of managing global supply chains?". Trade Ready. Retrieved

- ^"The impact of global value chains on rich and poor countries". Brookings. Retrieved

- ^Asghar, Ali; Kalim, Rukhsana (). "The Role of Institutions in the Economic Sustainability of Global Value Chains: A Transcendental Phenomenological Analysis of Pakistani Apparel Industry". Journal of Applied Economics and Business Studies. 3 (1): 1– doi/jaebs ISSN&#;

- ^"OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) Tables - OECD". www.oldyorkcellars.com. Archived from the original on Retrieved

- ^"World Input-Output Database". University of Groningen. Archived from the original on Retrieved

- ^Quast, Bastiaan; Wang, Fei; Stolzenburg, Victor; Reiter, Oliver; Krantz, Sebastian (), decompr: Global Value Chain Decomposition, retrieved

- ^Quast, Bastiaan; Kummritz, Victor (), gvc: Global Value Chains Tools, retrieved

External links[edit]

This excellent: Global value chains investment and trade for development

| 0.72 BITCOIN TO EUROS |

| Global value chains investment and trade for development |

| BEST WAY TO INVEST 1000 DOLLARS |

Global Value Chains and Investment: Changing Dynamics in Asia

The emergence of global value chains (GVCs) during the last 2 decades has implications in many policy areas, starting with trade, investment, and industrial development. The East and Southeast Asia region are key players in the GVCs and account for % of the global inward foreign direct investment (FDI) stock. GVCs are becoming increasingly important in the services sectors, although they are still less developed than in manufacturing.

GVC integration since the global financial crisis has continued to increase, but it is still too early to say to what extent GVC integration has been affected by the coronavirus disease (COVID) pandemic as rigorous data will only come out with a delay of some years.

Value chains are relatively robust to unexpected changes in trade costs. While the economic shocks related to COVID are indeed severe, the implications of the pandemic are more macroeconomic in nature, with some differences across sectors. The incentive to source goods locally versus using foreign suppliers has not been fundamentally altered.

The policy risk related to reshoring and the change in production locations may also be low. A more likely scenario is targeted interventions in sectors that have assumed particular importance during the pandemic, such as health-related goods and vaccines. Policy responses to the COVID pandemic must recognise the universal nature of the shock. It has affected all countries at essentially the same time, and had broadly similar effects in each of them, at least in its early stages. In this context, trade and investment policies require special review. In the GVC context, trade facilitation can increase backward and forward linkages. Similarly, restrictions on FDI can impair backward GVC participation.

More domestically focused supply chains may not be the right approach to post-COVID GVCs as they are poor shock absorbers. However, supply chain resilience is important for the production of public best investment app for beginners and public health necessities. Any policy intervention must balance the efficiency advantages of GVC production against social objectives.

East and Southeast Asia face a bigger risk in the slow recovery in large, high-income markets of Europe and the United States. Macro-level risks are relatively low, but at a micro level many countries continued use of non-traditional trade policies to introduce de facto discrimination against international suppliers may be a challenge ahead. The major potential change in conditions facing GVCs is the rise of the digital economy; East and Southeast Asia is well positioned to take advantage of these opportunities. Keeping markets relatively open, an effective supplier network, and integrated GVCs are important advantages for Southeast and East Asia in developing the GVCs of the future.

Full Report

GVC and Investment: Changing Dynamics in Asia

Contents

Title page

Table of Contents

List of Figures and Tables

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 2: GVCs and Investment in Asia: Changing Dynamics and Emerging Trend

Chapter 3: Trade and Investment Policies: Shaping the Global value chains investment and trade for development of GVCs

Chapter 4: Post-Covid GVCs in Asia

Chapter 5: Conclusions and Policy Implications + References

About the Authors

<< Back

Источник: [www.oldyorkcellars.com]Global value chain

A global value chain (GVC) refers to the full range of activities that economic actors engaged in to bring a product to market.[1] The global value chain does not only involve production processes, but preproduction (such as design) and postproduction processes (such as marketing and distribution).[1]